David Nexon, Academy Member

Health Security: Problems and Potential Solutions

The protection against the high cost of health care is an important aspect of income security. As the original Committee on Economic Security’s report stated, “A program or economic security … must have its primary aim the assurance of an adequate income…in sickness or in health….” Indeed, President Roosevelt originally intended to include a program of universal health insurance as part of the broad program of social protection the Committee’s report was designed to recommend. The health insurance plan was dropped only because of a political judgement that opposition from the American Medical Association and other groups would be so fierce that it could bring down the whole program.

Health security has two components. First, there must be adequate protection to assure that the cost of needed care will not constitute such a large drain on a families’ incomes as to endanger their savings and their standard of living. Second, the cost of care must not be so high that individuals unduly delay or go without needed treatment.

The primary source of health security is health insurance, although the health insurance that covers most Americans is not always adequate to provide true health security. Health insurance in the United States is provided largely through four mechanisms.

- Employer-provided insurance. Most of the population under 65 receive employer-provided health insurance through a job – directly as an employee or indirectly as a dependent of an employer. Fifty-four percent of the under 65 population – 178 million people – received coverage through an employer in 2021.i

- Medicare. Almost all elderly individuals and many people with disabilities receive government provided health care through Medicare—a classic social insurance program financed by payroll taxes, premiums, and general revenues. Medicare covered 64 million Americans in 2021.ii

- Medicaid. The joint federal-state Medicaid covered 64 million low-income citizens at the beginning of 2020—and provided supplemental coverage for over 11 million low- income Medicare enrollees. An additional seven million low-income children were enrolled in the Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP).iii Excluding the 11 million Medicaid enrollees who are also enrolled in Medicare, the number of people whose primary source of insurance is Medicaid or CHIP was approximately 60 million.

- Private individual insurance. Finally, 16.9 million people receive coverage by buying private insurance as individuals.iv Almost seventy five percent of this group receives premium and, in some cases, cost-sharing assistance through the Affordable Care Act (ACA).v, ACA enrollment has been significantly boosted by temporarily enhanced premium subsidies enacted under the American Rescue Plan in 2021 and extended through 2025 by the Inflation Reduction Act. vi

Health security remains elusive for millions despite these public and private health insurance programs. In 2021, 27 million Americans had no insurance for the entire year, and 37 million had no insurance for part of the year.vii These figures, however, are a significant underestimate of those who lack health security, as much of the insurance that people do have is inadequate, relative to their income, to provide protection against the high cost of health care. Some measures of health insecurity include:

- Almost one-quarter of the entire population (24 percent) reported that they went without needed health care in 2021 because they could not afford it. Forty percent of the uninsured reported this, but so did 22 percent of the insured. viii Moreover, many of those without adequate protection likely did not need health care in the year the surveys were conducted, and many others may have received care but faced great difficulty in paying for it.

- Significant health needs are often not covered by traditional health insurance or covered in a very limited way, including:

- Long-term care in nursing homes and at home.—less than 7 percent of individuals over age 50 have long-term care coverage, despite estimates that over 50 percent of Americans living beyond 65 will develop a need for long-term services and supports (LTSS). ix, x Annual costs of LTSS in 2021 ranged from $20,280 for adult day health care to $108,405 for a private room at a nursing xi

- Dental care—50 percent of adults do not have dental insurance, and only 2 percent of people over age 65 have dental insurance.xii, xiii In 2022, more than half of adults with an oral health problem did not seek care, and a quarter of these adults cited cost as the preventing factor.xiv

- Vision care— Medicare generally does not cover vision care except for cataract surgery. Over 50 percent of adults do not have vision insurance.xv

- Hearing care—Medicare does not cover the cost of hearing aids, which range in cost from $2,000 up to $7,000 per set.xvi The recent approval by the FDA of over- the-counter hearing aids may make the devices more accessible for some of the hearing impaired, but many will still require custom fitting by an audiologist and more sophisticated devices. Many commercial plans do not cover hearing aids either or only provide partial coverage.

- As discussed further below, the combination of deductibles and premiums, can place heavy burdens on insured families and contribute to so many families with insurance going without needed care.

- 79 percent of physicians report that high deductibles drive cost concerns among patients, and 80 percent believe that “their patients often or sometimes refuse or delay care due to cost concerns.” xvii

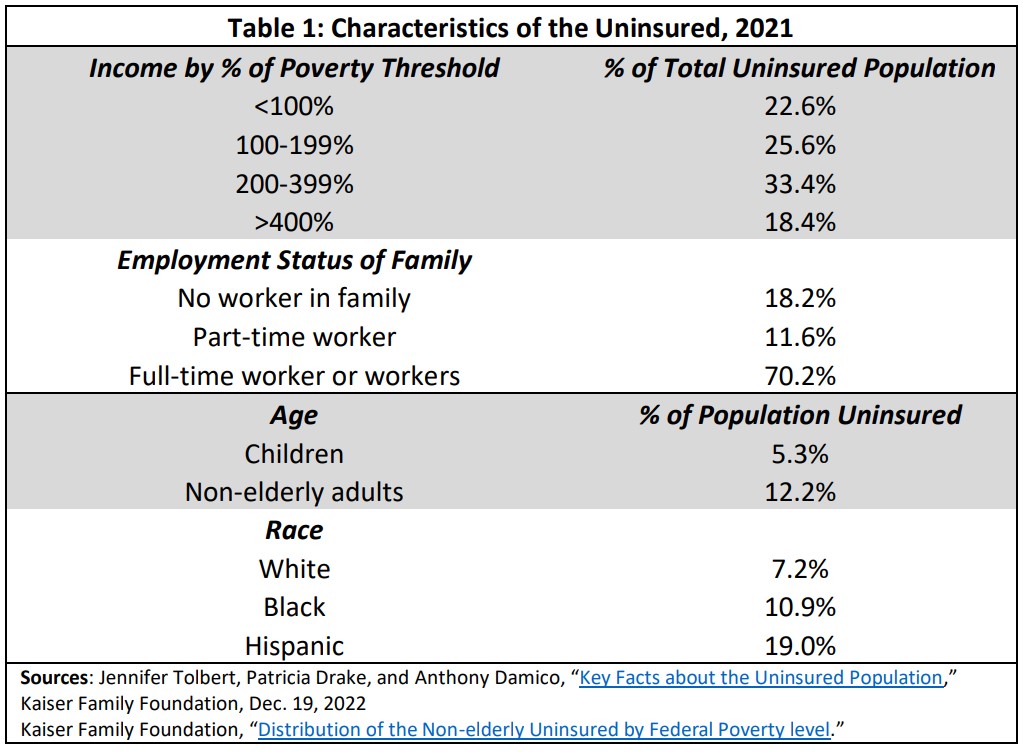

While many within the insured population are health insecure, none feel health insecurity more acutely than the uninsured. As noted above, 27 million Americans were uninsured for the entire year in 2021.xviii The number who were uninsured for some period of the year was significantly larger, 37 million.xix While programs like the Community Health Centers can provide subsidized primary care for some of the uninsured, lacking health insurance generally means that care will be unaffordable and that needed care often will be delayed until it escalates into an emergency. Table 1 provides data on uninsured individuals in the United States.

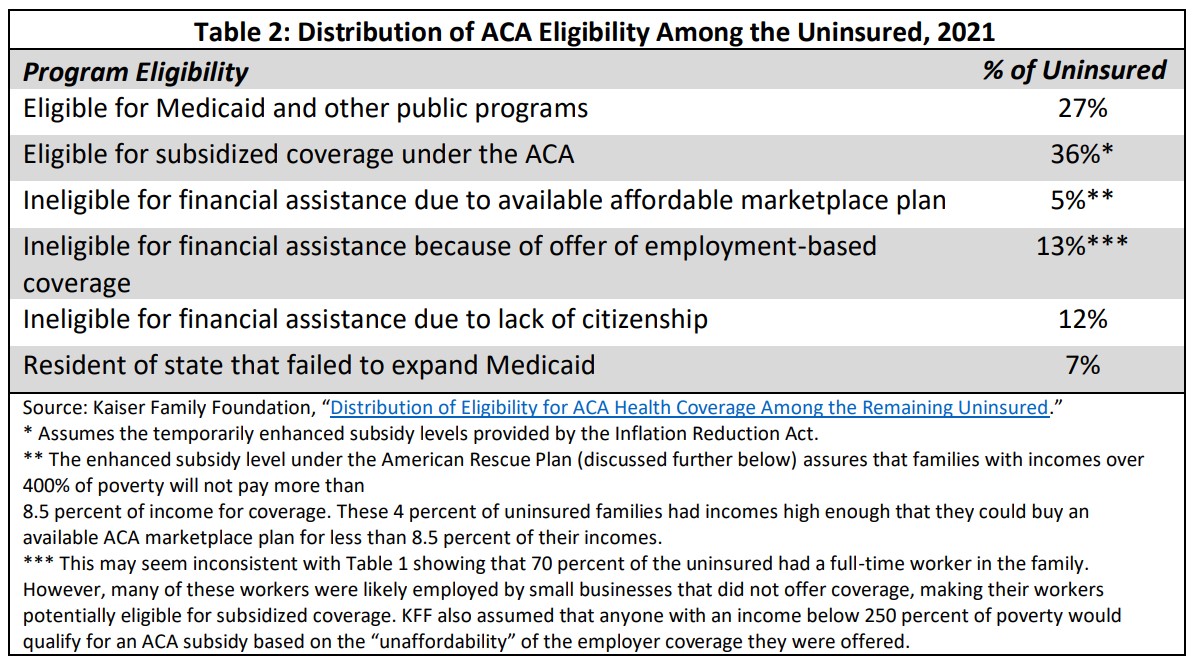

Many of the uninsured are eligible for coverage under existing programs. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), which is discussed further below, requires large employers (those with more than 50 full-time employees) to offer insurance to their workers, establishes a system of subsidized private insurance for those without access to employer-provided coverage, and provides incentives for states to expand Medicaid. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated uninsured individuals’ eligibility for coverage as shown in Table 2.

The next two sections more closely inspect the major vehicles that provide and supplement health insurance in the United States to understand first, why the current system results in widespread health insecurity and second, what measures might be taken to assure health security for all.

Overview: Limitations of Each Major Source of Insurance

Employer-provided insurance. While employment-based coverage is generally of good quality, this is not universally true. Coverage that is adequate for average-income employees often does not provide health security for lower income workers. High deductibles can pose a substantial barrier to care in both individual plans and employer-provided plans.

Medicare. While Medicare provides near universal coverage for the elderly and for many of the disabled, the combination of gaps in coverage, premiums, deductibles, and the lack of an out- of-pocket cap means that many beneficiaries still face unreasonably heavy demands on limited incomes.

Medicaid. Medicaid generally provides comprehensive coverage with no cost-sharing and no premiums. In the 10 states that have not expanded Medicaid coverage, however, childless adults with incomes below the poverty level are typically ineligible for Medicaid (unless they are aged, blind or disabled).xx Even adults with children are eligible only at very low income levels. These individuals are also generally ineligible for subsidized coverage under ACA private insurance plans even though people with incomes of 100 percent of poverty or more are eligible. This occurred because the authors of the ACA assumed all states would expand Medicaid coverage to cover these populations (a subsequent Supreme Court decision found unconstitutional the requirement that states conduct this expansion as a condition of receiving any Medicaid funds). Additionally, some important services that are optional for states—adult dental care is perhaps the most important—are not universally provided.

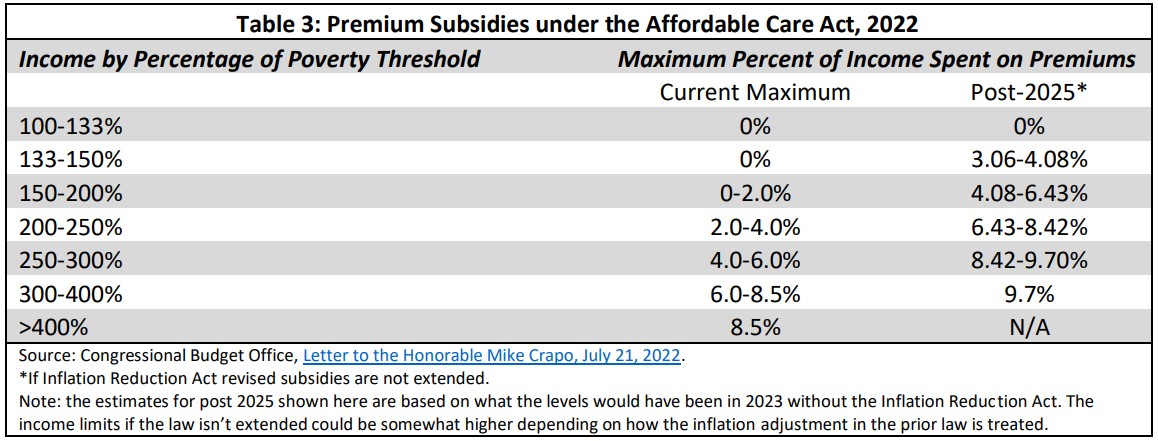

Individual health insurance. The ACA assures the availability of individual health insurance plans for people who are ineligible for Medicaid or Medicare, and those who do not qualify for “affordable” employer-provided insurance. The standards for individual coverage under the ACA do not, however, assure that insurance is affordable, that it provides adequate protection against high medical costs, or timely access to needed care.xxi This is especially for true for households ineligible for cost-sharing assistance (incomes above 250 percent of the poverty levels), but even those eligible can face substantial financial burdens. Under the American Rescue Plan, premium assistance was made temporarily available to families at all income levels (previously no protection was provided to families with incomes above 400 percent of poverty) and the premium subsidy levels for all families were substantially improved. This enhanced premium protection was extended through 2025 under the Inflation Reduction Act, passed in 2022.

The Issues in Depth: Understanding the Gaps in Order to Craft Solutions

Employer-provided insurance

The bulk of the under 65 insured population receives their coverage through an employer plan. The ACA requires large employers (with more than 50 full-time workers) to provide coverage, but the requirements are fairly minimalxxii:

- The employer plan must have an actuarial value of at least 60 percent (equivalent to a bronze plan) as defined in the ACA. Employees may therefore be liable for up to 40 percent of costs.xxiii (Features of the ACA plans, which range from bronze to silver to gold to platinum are described in more detail in the section below on the Affordable Care Act and Individual Private Insurance.)

- Coverage of the ten essential benefits (described below) that are required for individual plans under the ACA are not required.xxiv

- The maximum out-of-pocket charges for covered services are the same as required for individual plans under the ACA–$9,100 in 2023

- Employers are barred from imposing annual or life-time limits on the cost of covered services.

- Plans must meet an affordability standard for premiums charged to workers for coverage, but the limit set by the affordability standard is quite high—no more than 9.12 percent of family income (in 2023).xxv

While small businesses are not required to offer a health plan, any plan sold to them by an insurance company must cover the ten essential benefits, have no lifetime or annual limits, and return 80 percent of premiums in medical benefits, as well as conforming to any requirements of the state in which they are offered.

In practice, coverage for employer plans is fairly good for typical workers. A broad array of benefits is covered. A study by the Actuarial Research Corporation for the Department of Labor found that the average actuarial value of employer plans was between 82 and 84 percent (slightly better than an ACA exchange gold plan).xxvi The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that, in 2017, employer plans with low actuarial values were rare. The average actuarial value for the lowest five percent of employers was between 67 and 71 percent, close to the silver plan level. Thirty percent of employers offered coverage that was close to or above 90 percent.xxvii In 2017, the median out-of-pocket maximum for employers with more than 100 workers averaged $2,250. At the high end (90th percentile), the average was $5,100. Family out- of-pocket maximums for employer plans were typically twice the individual maximum.xxviii

At the same time, protection for low-income workers is much less robust. Workers with incomes below 200 percent of poverty enrolled in their employer plan paid an average of 10 percent of income for premiums and out-of-pocket costs; those with incomes between 200 and 400 percent of poverty paid almost 7 percent. For workers with a family member in poor health, the lowest income workers paid 14 percent of income and workers between 200-400 percent of poverty income paid 9.4 percent.xxix Of course, the burden for individual families could be much higher than the average. A family that hit the high-end family maximum and paid the average worker share of premiums ($6,106) would have to spend a total of $16,306 out-of-pocket and would have to earn more than $160,000 to keep their costs below 10 percent of income.xxx A worker earning the median amount of $55,640 in 2022, would have spent almost 30 percent of her income.

There has also been a strong trend toward employer adoption of plans with high deductibles. In 2022, among the 88 percent of workers in plans with deductibles, sixty-one percent had deductibles in excess of $1,000 and 49 percent faced deductibles in excess of $2,000. After taking account of employer contributions to health savings accounts or health reimbursement accounts, which employees can use to pay for cost-sharing, the proportion of workers with a deductible exceeding $1,000 was still more than half—54 percent, and 38 percent still faced a deductible exceeding $2,000.xxxi

Medicare

Medicare, enacted in 1964, is a social insurance program providing health insurance to 96 percent of the elderly. It also provides coverage to the disabled qualifying for Social Security disability insurance payments after a two-year waiting period. It covers a set of services generally typical of private insurance.

There are, however, some important gaps. Medicare has no out-of-pocket limits on spending, unlike private insurance policies.xxxii Full coverage of hospital care is limited to sixty days per episode of hospitalization, with substantial copayments for longer stays.xxxiii The hospital deductible is quite high–$1,408 per admission in 2021. There is a co-payment of 20 percent for physician and some other outpatient services, as well as a deductible of $203. If physicians refuse to “accept assignment”—that is, take Medicare rates as payment in full for services— beneficiaries can be charged more than 20 percent.xxxiv Premiums are set to cover 25 percent of Part B costs and have risen with the cost of health care. In 2021, these were set at $148.50 a month–$1,782 per year–for most beneficiaries. A couple pays a separate premium for each member of the family, and there is also a separate premium for those enrolling in prescription drug coverage.

The Medicare benefit package lacks some key services especially important to the elderly: coverage of hearing aids and routine hearing examinations, dental care, and routine eye exams and glasses. The most glaring omission is long-term care. While this is a gap common to most private insurance policies, it is a need that is most common among the elderly.xxxv

There are some mitigating factors to addressing these problems. Low-income beneficiaries who are eligible for Medicaid have medical costs not covered by Medicare that are covered by Medicaid. There are additional programs for low-income elderly with incomes above the Medicaid cut-off that provide assistance with premiums, co-payments and deductibles or premiums only.xxxvi One-third of beneficiaries have joined Medicare Advantage plans—private insurance plans that receive Medicare payments and often offer reduced cost-sharing with no additional premiums. Membership in these plans, however, means that patients no longer have free choice of providers. Many beneficiaries buy supplemental insurance that covers all or a portion of Medicare co-payments and deductibles as well as the cost of long hospital stays; the premiums for this insurance, however, adds to beneficiaries’ total costs. Twenty-nine percent of beneficiaries buy supplemental coverage; another thirty percent have supplemental coverage through an employer, which wraps around Medicare; and 22 percent have Medicaid coverage. The remaining six million beneficiaries with no coverage beyond Medicare—almost 20 percent—typically have modest incomes ($20,000-$40,000) and are age 85 or older.xxxvii

Despite these mitigating factors, the cost of health care poses heavy burdens for many of the elderly and disabled. An analysis of the 2015 tax returns of Medicare beneficiaries found that more than half of elderly beneficiaries claimed the deduction for out-of-pocket health expenditures in excess of 10 percent of income. More than four million out of nine million disabled Medicare enrollees also claimed the deduction. A separate data source found that those with costs more than 10 percent of income were typically of low or moderate incomes— 23 percent had below poverty incomes and almost 40 percent had incomes below 150 percent of poverty.xxxviii In 2013, half of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare spent at least 14 percent of their total per capita income on out-of-pocket costs; more than one-third (36 percent) spent at least 20 percent. By 2030, this was projected to rise to 42 percent of beneficiaries.xxxix

Medicaid

As noted earlier, Medicaid generally provides fairly comprehensive benefits to low-income Americans. In the ten states that failed to expand coverage in response to the Affordable Care Act, however, many low-income adults are excluded from coverage. No childless adults are eligible in these states unless they are aged, blind, or disabled. Coverage even for adults with children is extremely limited. The median income in these states below which parents must fall to be eligible for Medicaid is 43 percent of the federal poverty level.xl Approximately 3.7 million people would be eligible for Medicaid coverage if these states expanded coverage.xli

Adults with incomes below 100 percent of poverty are also ineligible for subsidized private insurance coverage because the ACA authors assumed all states would expand Medicaid. As the result of some glitches in the legislative process, adults with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of poverty, who were also assumed to be covered by expanded Medicaid, are eligible for subsidized private insurance coverage through the health care exchanges established by the law, as described above. Subsidized exchange coverage does not provide quite as much financial protection as Medicaid coverage, however, since premiums are not allowed under Medicaid unless a state has been granted a waiver and cost-sharing is restricted to “nominal” amounts. Most states do not impose any cost-sharing for Medicaid beneficiaries. Moreover, since there is no premium obligation and thus no concern people would delay enrollment until they are sick, Medicaid generally allows enrollment at any time, not just at specified open enrollment periods.

The combined mandatory and optional services under the Medicaid program are quite comprehensive. States have generally covered most optional services, but there are some important exceptions. Only 25 states and DC provide comprehensive coverage of adult dental services.xlii A few states omit other important services that would be considered basic in most insurance plans, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.xliii

The Affordable Care Act and Individual private Insurance

The ACA established four different levels of individual private insurance: bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. These levels are defined by the actuarial value of the coverage. The bronze plan covers an average of 60 percent of the cost of covered services, with the remainder paid by the individual or the family. The silver plan covers 70 percent, the gold plan 80 percent, and the platinum plan 90 percent. Cost-sharing subsidies, however, are available only for silver plans. Premium subsidies are based on premiums for silver plans but can be applied to the purchase of any metal plan. Within these actuarial values, plans can structure copayments and deductibles as they choose, except that out-of-pocket costs may not exceed statutory limits. In addition, a plan may not impose annual or lifetime limits on the cost of covered services. All plans must offer ten “essential benefits,” as defined in the statute and regulations.xliv All individual private insurance plans must meet these standards, whether offered on or off the health exchanges established by the law, but cost-sharing subsidies are available only for silver plans purchased on the exchange.xlv

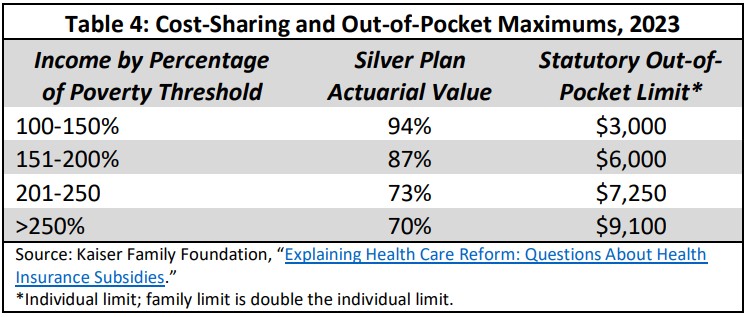

As noted above, cost-sharing subsidies that reduce the out-of-pocket obligations of individuals and families are available for those up to 250 percent of the poverty level, and premium subsidies are available for all income levels until 2026. Table 3 shows the premium subsidy schedule.

Copayments and deductibles continue to be set by the plan for those eligible for cost-sharing subsidies, but these are effectively reduced by a formula that increases the actuarial value of the plan for qualified lower income individuals. The ACA also sets limits on total annual out-of- pocket costs. In 2023, these were $9,100 for an individual and $18,200 for a family.xlvi These are reduced for lower income enrollees. The increased actuarial value of the plans at different income levels is shown in the table below, as are the allowable out-of-pocket limits:

Typical out-of-pocket limits for silver plans were generally close to the statutory limit, averaging $8,209 in 2019.xlvii

A second problem—which results from the relatively low actuarial value of the silver plan—is high deductibles. The average deductible for an unsubsidized silver plan was $4,753 in 2022. For individuals between 200 and 250 percent of poverty, whose cost-sharing is subsidized, the deductible was $3,215. For those 150-200 percent of poverty, it was $756, and it was $146 for those below 150 percent of poverty.xlviii A single individual at 225 percent of poverty would have to spend 10.2 percent of income before receiving any medical benefits, not including premiums. An individual at 251 percent of the poverty level would have to spend 14 percent. If average silver plan premiums are included, the individual at 251 percent of poverty would have to spend 18 percent of income before receiving any benefits.xlix

Beyond the impact on the family budget, high deductibles discourage people from seeking timely care. A study of a matched group of women switched to high deductible employer plans found that the high deductible group experienced a potentially life-threatening delay in seeking breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, including delays in first imaging, biopsy, diagnosis, and chemotherapy. The delay for lower income women compared to the control group was 8.7 months; even for the higher income group the delay was significant—5.7 months.l High deductible plans were defined as those with a deductible of $1,000 or more for the purposes of this study. Other studies of high deductible plans showed similar impacts.li

The combination of a relatively low actuarial value for a silver plan, relatively high out-of-pocket limits, and, at least prior to the American Rescue Plan, less than generous premium subsidies, means that, for many families, medical costs can still create a crushing burden.

This burden will worsen further if the American Rescue Plan and Inflation Reduction Act enhanced premium subsidies are not extended. Modeling of medical costs for people at different levels under the subsidy scheme in place prior the American Rescue plan found that significant numbers of families at all levels of income above 150 percent of poverty were exposed to costs in excess of 20 percent of family income.lii

Conclusion

Health security is an essential component of economic security, and quality health insurance is the primary vehicle for providing health security. Our current system of health insurance relies on four principal vehicles: employer-provided health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and individually purchased health insurance.

There are, however, large gaps in this system. Prior to the COVID epidemic, there were 37 million people without any insurance at all for at least part of the year. Among the insured, inadequate insurance is widespread.

There are several different approaches that could be taken to address this problem.

Health security could be addressed by establishing a new, universal tax-financed social insurance program which aims to provide health security to all. Versions of this approach in the U.S. have often been referred to as “Medicare for All.”

Alternatively, the gaps in the existing structure could be filled with improvements to current programs. Components of this approach might include:

Employer-provided insurance.

- Expand the requirements for employer-provided insurance to parallel the minimum requirements for improved ACA individual coverage, including:

- a higher actuarial value requirement,

- equivalent subsidies for low-income workers,

- and coverage of essential benefits.

- Alternatively, allow any worker to choose individual coverage under the ACA if it would offer better protection than the employer plan, with a substantial employer contribution to the cost of this coverage.

Medicare.

- Include an out-of-pocket maximum on cost-sharing.

- Provide additional premium and cost-sharing assistance for low-income beneficiaries.

- Expand the benefit package to include dental, vision, and hearing.

- Address the need for long-term care coverage through a separate social insurance program.

Medicaid.

- For states that have refused to expand Medicaid coverage, provide equivalent federal coverage for the expansion population.

- In order to be fair to states that have already expanded coverage, raise the match rate for the expansion population from 90 to 100 percent.

- Enhance efforts to prevent eligible enrollees from losing coverage through administrative and outreach failures.liii

- Make most Medicaid optional services mandatory.

ACA individual coverage.

- Improve the standards for the basic subsidy-eligible plan offered under the ACA (to a “gold plus” level) that will bring the unsubsidized deductible below $1,000 and lower out-of-pocket maximums to affordable levels.

- Enrich cost-sharing subsidies and provide them at least to levels of income below 300 percent of poverty.

- Make the premium subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act permanent.

- Add adult dental care to the ten essential required benefits.

- Give the Secretary the authority to add additional benefits by regulation.

Immigrants.

- Make undocumented immigrants eligible for all health programs on the same terms as citizens.

Encourage enrollment.

- Expand outreach programs and use enrollment in other assistance programs, such as food stamps or school lunch programs, to identify eligible uninsured individuals.

- For employer plans, introduce an opt-out rather than an opt-in structure such that employees are automatically enrolled in a plan unless they opt out.

- Require employers to provide information of the availability of ACA and Medicaid plans to employees.

- Require employers to inform enrollment facilitators of the contact information of employees who are uninsured.

David Nexon is President of Nexon Policy Insights, the former Democratic Health Policy Staff Director for the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, and the former Senior Health Policy Advisor to Senator Edward M. Kennedy.

Endnotes

i U.S. Bureau of the Census, “Health Insurance Coverage in the U.S. 2021,” September, 2022

https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-278.pdf

ii Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “CMS releases latest enrollment figures for Medicare, Medicaid, and

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Dec. 21, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/news-alert/cms-releases-latest-enrollment-figures-medicare-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip

iii Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “July 2022 Medicaid and CHIP enrollmentSnapshot.” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/downloads/july-2022-medicaid-chip-enrollment-trend-snapshot.pdf. Driven in part by the coronavirus epidemic and temporary federal rulesrequiring continuous coverage of people once they are enrolled by Medicaid, coverage had soared to 82 million by July 2022, an increase of 28 percent just since February, 2020. An additional 7 million children were enrolled in the Child Health Insurance Plan(CHIP) which layers on top of Medicaid for low income children. An additional 12 million people who receive primary coverage through Medicare receiveMedicaid supplemental assistance.

iv Jared Ortaliza, Krutika Amin, and Cynthia Cox. “As ACA Marketplace Enrollment Reaches Record High, Fewer AreBuying Individual Market Coverage Elsewhere,” Kaiser Family Foundation, Oct. 17, 2022. https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2022-Annual-Survey.pdf

Excludes a small number of people enrolled in plans that do not meet ACA standards, e.g., short-term plans, dread diseaseplans, dental only plans, etc.

v Ibid.

vi The previous and revised subsidy schedules are shown in a letter from the CBO toSenator Mike Crapo, the ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee on July 21, 2022. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58313.

vii U.S. Census, Current Population Survey, Health Insurance Coverage in 2021, Table H-03. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hi/hi.html.

vii “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021,” Board of Governors ofthe Federal reserve System, May 2022. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2021-report-economic-well-being-us-households-202205.pdf. These figures were virtually unchanged since 2018, so they were apparently notsignificantly affected by the Covid epidemic.

ix “Combination Products Giving Life Back to Long-term Care Market,” LIMRA, November 2017. https://www.limra.com/en/newsroom/industry-trends/2017/combination-products-giving-life-back-to-long-term-care-market/.

x Melissa Favreault and Judith Dey. “Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans:Risks and Financing Research Brief,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Servies, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation,February 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/long-term-services-supports-older-americans-risks-financing-research-brief-0.

xi “Cost of Care Survey,” Genworth, 2021.

https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html.

xii Debra L. Blackwell, Maria A. Villarroel, and Tina Norris. “Regional Variation in Private Dental Coverage and Care Among Dentate Adults Aged18–64 in the United States, 2014–2017,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center forHealth Statistics, May 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db336-h.pdf.

xiii “Data Brief 337. Dental Care Among Adults Aged 65 and Over, 2017,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2017.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db337_tables-508.pdf#page=1.

xiv Lisa J Heaton, Adrianna C Sonnek, Kelly Schroeder, and Eric P. Tranby. “Americans Are Still Not Getting theDental Care They Need,” CareQuest Institute for Oral Health, April 2022.

https://www.carequest.org/system/files/CareQuest_Institute_Americans-Are-Still-Not-Getting-Dental-Care-They-Need_3.pdf.

xv “The Vision Council Releases VisionWatch Q4 2021 Market Research Reports,” The Vision Council, March 2022.

https://thevisioncouncil.org/blog/vision-council-releases-visionwatch-q4-2021-market-research-reports#:~:text=126.8%20million%20U.S.%20adults%2C%20or,lives%20compared%20to%20December%202020.

xviAmber Willink, Nicholas S. Reed, and Frank R. Lin. “Why Easier Access to Hearing Aids Is Not Enough,” The Commonwealth Fund, January 2019.

XVII “PAI-NORC survey shows high deductible health plans are a barrier to needed care,” Physicians Advocacy Institute, June 2020.

XVIII U.S. Census, Current Population Survey, Health Insurance Coverage in 2021, Table H-03. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hi/hi.html.

XIX Ibid.

XX “Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map,” KFF, July 2023.

XXI Affordability under the ACA for 2023 is defined as a premium cost not exceeding 9.12 percent of household income. Prior to 2023, this standardonly applied to the cost of individual coverage, but the Biden Administration changed that by regulation to apply this standard to family coverage as well.

XXII There are also some requirements that preceded the ACA, including nondiscrimination, limits on pre-exiting condition exclusions, and requiredparity for mental health and physical health benefits.

XXIII “The health plan categories: Bronze, Silver, Gold & Platinum,” HealthCare.gov.

https://www.healthcare.gov/choose-a-plan/plans-categories/.

XXIV “What Marketplace health insurance plans cover,” HealthCare.gov.

https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/what-marketplace-plans-cover/.

XXV Prior to 2023, this standard only applied to individual coverage, with no limit on the cost of family coverage. The Biden Administrationcorrected that by regulation. If the premium cost for a worker would exceed this standard, the worker and his family could enroll in an ACA exchange planand take advantage of the subsidies available under that plan. Workers offered an employer plan that meets these standards are not allowed to enroll in anexchange plan, even if would provide more generous coverage at lower cost.

XXVI Actuarial Research Corporation, “Final Report, Analysis of Actuarial Values and Plan Funding Using Plans from the National CompensationSurvey,” Actuarial Research Corporation, May 12, 2017.

XXVII Bureau of Labor Statistics “Health and Retirement Plan Provisions in Private Industry in the United States,2017,” May, 2018. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/detailedprovisions/2017/ownership/private/health-retirement-private-benefits-2017.pdf.

XXVIII Bureau of Labor Statistics “Health and Retirement Plan Provisions in Private Industry in the United States,2017,” May, 2018. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/detailedprovisions/2017/ownership/private/health-retirement-private-benefits-2017.pdf.

XXIX Gary Claxton, Bradley Sawyer, and Cynthia Cox, “How Affordability of Health Care Coverage Varies by Income Among People with Employer Coverage.,”Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, April 14, 2019. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/how-affordability-of-health-care-varies-by-income-among-people-with-employer-coverage/.

XXX The average employee share of the premium comes from the Kaiser Family foundation, 2022 Employer Health Benefits Survey, October 22, 2022, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2022-employer-health-benefits-survey/.

XXXI Gary Claxton, et al., Employer Health Benefits Survey 2020 Annual Survey, Kaiser Family Foundation, section 7.

XXXII The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 added an out-of-pocket cap for out-patient prescription drug costs covered under Medicare.

XXXIII An episode of hospitalization is defined begins with an admission to a hospital or skilled nursing facility and ends after a 60 day period fromthe discharge from either a hospital or nursing home when there is no intervening readmission.

XXXIV A provider not accepting assignment on a claim can charge the beneficiary up to 15 percent more than the Medicare-approved amount. Since thebeneficiary is generally responsible for 20 percent of the Medicare approved charge, this almost doubles the beneficiary obligation. However, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 95 percent of physicians accepted assignment on all claimsin 2016. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_medpac_ch4.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

xxxv See the Benjamin W. Veghte, et al., Designing Universal Family Care: State-Based Social Insurance Programs for

Early Child Care and Education, Family and Medical Leave, and Long-Term Care Services and Supports, National

Academy of Social Insurance, June 2019, for a discussion of options for social insurance approaches to covering

long-term care.

xxxvi These programs are briefly described at https://www.medicare.gov/your-medicare-costs/get-help-payingcosts/medicare-savings-programs#collapse-2624.

xxxvii Juliette Cubanski, Anthony Damico, Tricia Neuman, and Gretchen Jacobson, “Sources of Supplemental

Coverage Among Medicare Beneficiaries in 2016,” Kaiser Family Foundation, Nov.28, 2018.

xxxviii Maxim Shvedov, “Seniors with High Unreimbursed Health Care Costs: Who Are They?” AARP Policy Institute,

November 2017. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017/10/seniors-with-high-unreimbursed-healthcare-costs.pdf.

xxxix Juliette Cubanski, Tricia Neumann, Anthony Damico, and Karen Smith, “Medicare Beneficiaries’ Our-of-Pocket

Health Care Spending Now and Projections for the Future.” Kaiser Family Foundation, Jan. 26, 2018.

https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/medicare-beneficiaries-out-of-pocket-health-care-spending-as-a-share-ofincome-now-and-projections-for-the-future/.

xl Jennifer Tolbert, Kendal Orega, and Anthony Damico, “Key facts about the Uninsured Population,” Kaiser Family

foundation, Nov. 6, 2020. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/.

The situation for children is somewhat different. States are required to cover children through the age of 18 in

families with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line. The Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP) is a

capped entitlement to states allowing them to cover children not eligible for Medicaid up to 400 percent of the

poverty line. Actual coverage is determined by the state and ranges from a low of 170 percent to 400 percent.

States have the option of using CHIP funds to provide coverage through their existing Medicaid program or a

separate private insurance program. The latter typically has fairly comprehensive coverage and low premiums and

cost-sharing.

xli Mathew Buettfens and Urmi Ramchandani, “3.7 Million People Would Gain Health Coverage in 2023 if the

Remaining 12 States Were to Expand Medicaid Eligibility.” The Urban Institute. August 3, 2022.

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/3-7-million-people-would-gain-health-coverage-2023-if-remaining12-states-were. South Dakota and North Carolina have just voted to expand Medicaid, reducing the number of

States that have not approved expansion to 10, but these expansions have not yet been implemented. Expansions

in these states would add an estimated 700,000 people to the Medicaid rolls.

xlii “State Medicaid Coverage of Dental Services for General Adult and Pregnant Populations,” National Academy for

State Health Policy, October 2022.

https://nashp.org/state-medicaid-coverage-of-dental-services-for-general-adult-and-pregnant-populations/.

xliii “Medicaid & CHIP,” KFF. https://www.kff.org/state-category/medicaid-chip/medicaid-benefits/.

xliv The ten essential benefits are (1) ambulatory patient services; (2) emergency services; (3) hospitalization; (4)

maternity and newborn care; (5) mental health and substance abuse disorder treatment; (6) prescription drugs; (7)

rehabilitative and habilitative services; (8) laboratory services; (9) preventive and wellness services and chronic

disease management; and (10) pediatric services, including oral and vision care. The ACA legislation directed

further that the services provided under these categories be equal to the benefits provided under a typical

employer plan; by regulation, this requirement was fulfilled by allowing a state to select benchmarks from four

options, including one of the three largest small group plans in the state, the state employee health benefits plan,

and of the three largest national Federal Employee Benefits program plan options, or the largest commercial HMO

in the state. Plans were allowed to adjust the scope and specific of benchmark plan benefits, but only if the result

was actuarially equivalent to the benchmark plan benefits in each category of benefits.

xlv An exception is so-called “short-term” insurance plans. These were originally supposed to last only three months

but the Trump Administration promulgated rules allowing them to last one year and to be renewable.

xlvi CMS, https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/out-of-pocket-maximum-limit/

xlvii https://www.kff.org/slideshow/cost-sharing-for-plans-offered-in-the-federal-marketplace/.

xlviii Ibid.

xlix Calculated by the author from Ibid.

l J. Frank Wharam, et al. “Vulnerable and Less Vulnerable Women in High Deductible Health Plans Experienced

Delayed Breast Cancer Care,” Health Affairs, March 2019.

https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05026.

li For a further discussion and citations on this point, see David Nexon, “How To Build on the Affordable Care Act,”

the Century Foundation, Oct. 8, 2019, p. 10. The impact of deductibles on at least initial care-seeking is mitigated

somewhat for silver plan enrollees by exclusion of certain services from the deductible. In 2016, 80 percent

exempted primary care visits and generic drug prescriptions, 64 percent exempted office visits to specialists and

brand name drug prescriptions, and 63 percent exempted mental health outpatient visits. In addition, the ACA

requires that certain preventive services have no associated cost-sharing. Munira Z. Gunja, et al., “How Deductible

Exclusions in Marketplace Plans Improve Access to Many Health Care Services,” The Commonwealth Fund, March

17, 2016. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/mar/how-deductible-exclusionsmarketplace-plans-improve-access-many?redirect_source=/publications/issue-briefs/2016/mar/deductibleexclusions.

lii Modeling by Jon Gruber, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, using Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Data,

personal communication with the author.

liii Of those who lose Medicaid coverage, more than 80 percent are typically actually still eligible. ASPE, Office of

Health Policy, “Issue Brief: Waiving the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision: Projected Enrollment Effects

and Policy Approaches,” August 19, 2022.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/404a7572048090ec1259d216f3fd617e/aspe-end-mcaidcontinuous-coverage_IB.pdf

Thanks to David Nexon for this superb comprehensive description of health security policy options.

–Bill Arnone

Thank you for sharing wonderful insights on health security policy options