By: Jay Patel

Published: May, 2020

Introduction

The U.S. workers’ compensation system in its current form is complex, opaque and fragmented. Unlike other social insurance programs, it is wholly administered at the state level, and there is neither federal oversight nor any federal mandate that sets out minimum standards. As a result, there is substantial variation across states in levels of both coverage and benefits. Moreover, compensation differs for job-related injuries versus illnesses.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the challenge of determining whether employees who contract a highly contagious disease that exposes some workers more than others qualify for benefits under workers’ compensation. This brief explores how those two disparities – from state to state and between injuries and illnesses – are playing out during this crisis, and longer-term implications.

Occupational disease and Workers’ Compensation: A complicated relationship

There is a reason that workers’ compensation is known as the ‘grand bargain’ for employers and employees. In exchange for receiving cash benefits and medical care for covered injuries, illnesses, and death, regardless of fault, employees waive the right to sue their employers for these (non-intentional) consequences of workplace accidents.

Coverage has never been universal; from the start, certain classes of workers, in particular agricultural and home/domestic workers were excluded. In general, workers’ compensation coverage is required for employees whose employers are required to provide W-9 statements and who are also covered by state Unemployment Insurance programs. However, even some of these employees are excluded. Texas allows employers to “opt-out” of coverage, and in practice so does Wyoming for some large employers. More recently, the growing number of workers considered independent contractors and so-called “gig” workers join those who are excluded, reducing the total share of those covered to less than 87% of U.S. jobs (Boden, Murphy, and Weiss, 2019).

Moreover, in the early development of workers’ compensation in the U.S., occupational diseases were generally excluded from compensation.1 Reasons for the reluctance to compensate diseases varied among the states. The very prevalence of some diseases such as silicosis led to concerns that coverage would simply be too expensive. In some states, the courts and legislatures rejected coverage because diseases were generally not recognized by the earlier common law – and the compensation systems were viewed as simply replacing tort liability with non-fault systems.2 This was an ironic twist, considering the key role that occupational diseases such as phossy jaw, lead palsy, silicosis, and others played in the progressive movement’s efforts to establish workers’ compensation in the early 1900s (Abrams, 2001). In the rare instances in which occupational diseases were covered by statute, most courts denied the claims on technical grounds (Abrams, 2001).

A gradual movement toward coverage of occupational diseases began in 1915 in California, expanding to more than half of all states by 1939. Nonetheless, it remained difficult to obtain compensation for occupational disease claims. Indeed, the 1969 passage of the federal Black Lung Act was a reaction to organizing by the United Mine Workers of America and by coal miners suffering from coal workers’ pneumoconiosis who could not easily obtain compensation at the state level.

There are still stark differences between a “workplace injury” and an “occupational disease” with respect to the number of claims filed, rates of approval and denial of claims, benefit levels, and required evidence (Brandt-Rauf and Brandt-Rauf, 1988). Many occupational disease claims are never filed, due to long latency periods for some illnesses, lack of understanding of their work-relatedness, a paucity of medical providers who are willing to link patients’ illnesses with their work, and the low probability of receiving benefits. Insurers initially deny more than half of disease claims, compared to 10% to 20% of injury claims, with significant burdens of proof placed on employees who submit disease-based claims (Barth and Hunt, 1980; Brandt-Rauf and Brandt-Rauf, 1988).3 As a result, most occupational diseases are, in practice, not compensated (Burton and Spieler, 2012; Leigh and Robbins, 2004).

Quick Overview: How States Administer Occupational Disease Claims

States have taken various approaches to including occupational diseases in their compensation programs. Initially, this was done through expanding the understanding of what constituted an injury at work. In 1920, New York adopted a schedule-type act that listed covered diseases. This method was replicated elsewhere, but the trend has recently shifted toward general coverage, either by abandoning the listing schedule or by amending the statute so that the list of diseases does not foreclose the possibility of expansion to other diseases (Larson’s § 52.02).

General coverage of occupational diseases is usually achieved through a definition such as the following from Virginia law:

“…[t]he term ‘occupational disease’ means a disease arising out of and in the course of employment, but not an ordinary disease of life which the general public is exposed outside of employment…”

As is also true of injuries, an occupational disease must be work-related – “in the sense that the claimant’s work caused the condition” (Burton and Spieler, 2012). As the Virginia statute suggests, the individual claiming compensation must be able to prove that the disease arose out of and in the course of employment, that it was linked to a specific exposure that occurred within the scope of the worker’s duties, and that the work exposure put the employee at a greater risk of contracting the illness than is true for the general public. This means that the same illness can produce very different outcomes in workers’ compensation claims depending on the employee’s job responsibilities and exposures, where the claim is filed, the availability of experts to assist in proving a claim, and other factors.

Infectious diseases, such as the flu, are rarely compensated under the occupational disease statutes; they are not listed and they are often prevalent in the general community. These diseases may, however, be compensable if there is proof of an abnormal level of workplace exposure.5 For example, cases around the country have been approved for nurses who contracted infectious diseases such as tuberculosis in a tuberculosis sanatorium, smallpox in a smallpox isolation ward, or polio in the polio ward of a hospital (4 Larson’s § 51.05).

Because occupational disease claims have historically been difficult to prove, there have been political movements to try to create presumptions involving work causality in order to make it easier for workers to obtain compensation when they contract diseases known to be related to exposures at work. For example, a number of states have adopted legislation for “first responders” to provide compensation to fire fighters and similar front-line workers whose exposures put them at high risk for cardiac or respiratory diseases or specific cancers. Such provisions make it easier for these workers to successfully file claims by shifting the presumption of work-related causality in their favor (4 Larson’s § 52.07 (2019)).

The novel coronavirus reflects aspects of this complexity. It is highly contagious and considered an ordinary disease of life, but disproportionately exposes workers in specific occupations (not only health care providers and other hospital staff, but also bus drivers, grocery stockers, and workers in warehouses and meatpacking plants). Adding presumptions for COVID-19 is one method to tackle the issue, but it is unclear how overwhelmed state systems would be, if coverage is expanded for the full range of workers who are at higher risk.

How are state Workers’ Compensation agencies handling COVID-19?

COVID-19 is not included in any state’s list of occupational diseases (though New York is considering this option). Since these are independent state systems, each state can address the COVID-19 pandemic differently.

One common issue that all states face is the ‘ordinary’ nature of the disease – a disease that the general public is exposed to and can contract easily outside the workplace. For a claim to be approved for COVID-19 under workers’ compensation, unless a law is changed to make specific provision for the disease, a worker must show both that he or she contracted the illness at work and had a greater risk of exposure on the job than is true for the general public.

Except for very high-risk workers in the health care industry and similar jobs, this may be a difficult burden to meet in the context of the current pandemic, since the risk of community exposure is so high. Some states are responding by lowering the proof required for select groups of workers, so that the disease will be presumed to have been contracted at work and therefore be compensable. These changes are being made either by executive orders or through special legislation.

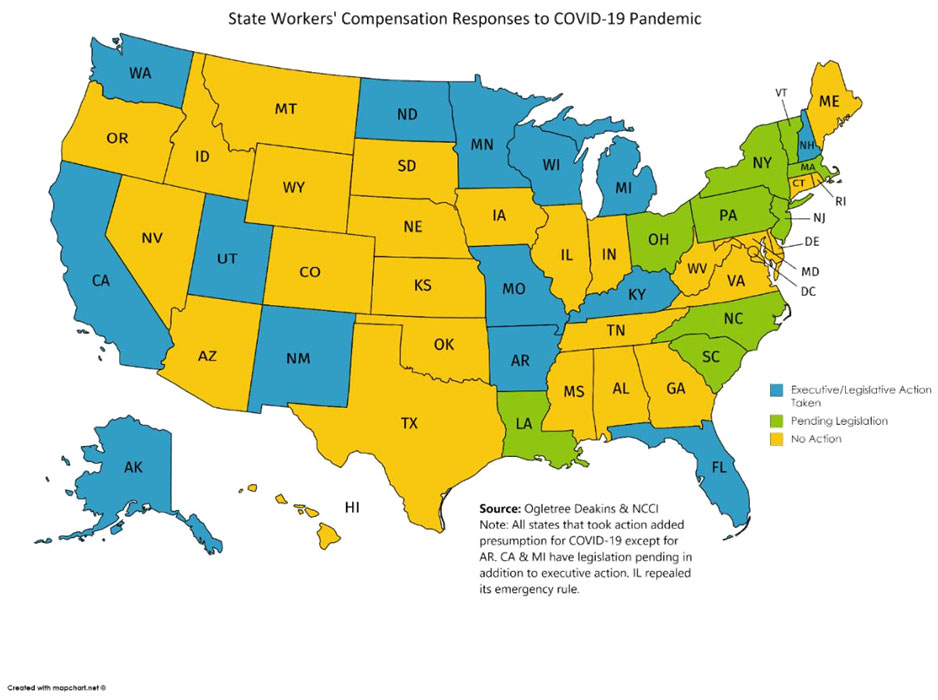

As of May 18, 2020, fourteen states have made these changes, and another nine are considering them. (See Appendix for a full list of each state’s response to the crisis.)6

Below, we provide examples of new guidelines that a few states have issued specifically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although not an exhaustive list, the selected states here showcase the variety of ways states are approaching the problem.

Washington78

Washington was the first state to report a confirmed case of the novel coronavirus and where the first U.S. outbreak began. It was also the first state to publish guidelines concerning workers’ compensation and COVID-19.

The clarifying guidelines issued by the Washington Department of Labor and Industries effectively expand workers’ compensation coverage to first responders (e.g., police and firefighters) and health care workers who have been advised to self-quarantine or diagnosed with COVID-19 by a physician or a public health officer. In other words, it creates presumptions for workers who are disproportionately exposed on the job and thus likely to have contracted the illness there. Workers’ compensation payments cease once a worker tests negative for COVID-19 or at the end of the fourteen-day quarantine. All other claims of exposure submitted will be considered on a case-by-case basis.

For claims submitted by employees who are not first-responders or who have not been advised to self-quarantine, the burden of proof remains high. Claimants must be able to trace a specific source or event that led them to contract the novel coronavirus while performing the duties of their employment. This does not preclude employees from filing a claim, but it will likely lead to a denial if the source is not traceable or if the worker cannot demonstrate that they contracted the virus through ‘doing their job.’ The guidelines conclude that “[i]n most cases [i.e., other than health workers and first responders], exposure and/or contraction of COVID-19 is not considered to be an allowable, work-related condition.”

Illinois10

The Illinois Workers’ Compensation Commission issued a broad emergency rule creating a rebuttable presumption of causality of work-relatedness for all essential workers enumerated in the state’s initial emergency order that allowed certain businesses to continue operation. The list includes first responders, health care providers, correction officers, and employees in a range of industries such as food production and agriculture, as well as retail stores that sell groceries, medicine, and hardware, gas stations, laundry services, restaurants providing off-site consumption, education, and others.

This emergency rule was immediately challenged by the Illinois Manufacturers and Illinois Retail Merchants Associations, arguing that the Commission exceeded its authority in passing the rules. A Sangamon County circuit judge granted a temporary injunction against implementation of the rule, and the case is pending. The issue may be moot, however, as the Commission immediately repealed the rule.

Other states in which governors, rather than the legislature, make changes to compensation by expanding coverage for private-sector workers, may face similar litigation.

Minnesota12

Unlike the other states described here, which changed their presumptions via executive orders, Minnesota’s legislature passed detailed legislation on April 10, 2020, regarding compensation for COVID-19. HF 4537 provides a presumption of COVID-19 causation to specified employees (first responders, corrections officers, home care employees, and others). To file a claim, the worker must provide a laboratory test confirming his/her contraction of the disease or be officially diagnosed by an appropriate healthcare worker as defined in the bill. Employers or insurers can rebut the presumption only by showing that the employment was not the direct cause, greatly shifting the burden of proof from employee to employer. Minnesota is also the only state to set an end date for the new legislation, sunsetting the COVID-19 provision on May 1, 2021.

New York

New York’s status as the ‘epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic’ makes it a logical choice to examine. Although New York has yet to enact or issue any rule changes, legislation, or executive orders that expands compensability for those diagnosed or quarantined with COVID-19, there is pending legislation in the state Senate that would address the issue in a unique manner. If passed, SB 8266 would add COVID-19 as an occupational disease under New York workers’ compensation law for a very broad class of employees in “any and all work that could expose workers to novel coronavirus.”13 As with other pending legislation discussed in this issue brief, it is impossible to know the likelihood of its passage.

California

California was the first U.S. state to have a case of local transmission, prompting the governor to order the first state-wide ‘stay-at-home’ order in the country, just four weeks later. Unlike Washington’s more muted approach, Californian legislators have introduced four bills (AB 196, SB 893, AB 664, and SB 1159) to address workers’ compensation and the coronavirus. All four bills are currently in committee, due at least in part to the suspension of California state legislative sessions under the stay-at-home orders.14 If passed, these bills would provide much-needed updates concerning compensability for occupational and infectious diseases under workers’ compensation law, along with precedent for future public health episodes.

Bills AB 196, AB 664, and SB 1159 each address workers’ compensation in the scope of the epidemic exclusively and do not make wide-spread changes outside this context.

- AB 196 creates conclusive presumptions for employees in occupations and industries that are deemed essential under the “stay-at-home” orders issued by the governor.

- AB 664 would provide a conclusive presumption for first responders (as defined in bill) and public and private health care workers in the exposure or contraction of communicable diseases (including COVID-19). Similar to Washington’s changes, the presumption also extends to the class of workers if it is directed to quarantine by a licensed health professional or public agency. However, AB 664 would only apply in cases in which the communicable disease in question is the subject of a state or local declaration of a ‘state of emergency’.

- SB 1159 provides a disputable presumption to all critical workers (private and public) employed to combat the spread of COVID-19 who meet criteria set in the bill.

The final piece of legislation in consideration, SB 893 (Workers’ Compensation: Hospital Employees), seeks to expand and amend workers’ compensation to address occupational diseases and conditions (e.g., MSRA, meningitis, novel pathogens) beyond COVID-19 or a similar epidemic. As the bill’s name implies, SB 893 is intended to cover hospital employees (those providing direct care in an acute hospital) and redefines the term “injury” to include infectious diseases, musculoskeletal injuries, and respiratory diseases (including COVID-19) as defined in the bill. It provides a rebuttable presumption in recognition of the higher rate of work-related injuries and illnesses that nurses experience relative to other categories of workers.

In addition to this pending legislation, the governor has issued a sweeping order regarding the compensability of coronavirus in workers’ compensation. On May 6th, Governor Gavin Newsom signed Executive Order N-62-20, creating a rebuttable presumption that an employee’s COVID-19-related illness arose out of and in the course of employment and thus qualifies for worker’s compensation benefits. To be eligible for the presumption, the employee must either (1) test positive for COVID-19 within 14 days after performing work or (2) be diagnosed (within 14 days of performing work) by a California-licensed physician and have that diagnosis confirmed within 30 days of the original diagnosis date via a laboratory test. The presumption does not cover employees working from their own homes, applies only to cases occurring from March 19 to July 6, 2020, and does not prevent insurance carriers from adjusting the costs of their policies.

Conclusion

The challenges, even in ordinary times, posed by occupational disease versus injury claims are likely much more difficult for both workers and employers to understand and navigate during this crisis. Now they are further complicated by the spectrum of stay-at-home and reopening orders issued by governors across the country who are struggling to balance the public health and economic aspects of the crisis and landing in different places.

The decentralized nature of workers’ compensation requires that each state address the degree to which COVID-19 is covered as an occupational disease. In general, current law suggests that, other than those in particularly risky jobs, even workers in industries that have been deemed “essential” who fall ill with COVID-19 are unlikely to receive workers’ compensation.20 While executive orders include those stocking shelves, bus drivers, and meatpacking workers, the emergency orders and legislation that are under consideration in many states only extend to employees in health care and first responders. As is true of unemployment insurance, this pandemic has also made clearer the problems caused by lack of coverage for independent contractors and so-called “gig” workers.

More generous workers’ compensation policies for COVID-19 could improve economic security for many workers. These could be particularly important for workers who have lost their health insurance during the pandemic. But they could also place a substantial burden on employers and insurers, especially if the rate of infection continues to climb.

Moreover, as governors and business owners have expressed, choices regarding compensability and reopening may expose the owners and others to lawsuits brought by workers who assert grounds to go outside of the workers’ compensation system. While the “grand bargain” insulates employers and their insurance carriers from such suits in most cases, it has important exceptions.22 For example, it does not protect a contractor hired to install a ventilator system that turns out to be defective in protecting workers from COVID-19 exposure. Most significant, all states extend an exception to the exclusive remedy provision to situations in which an employer shows reckless disregard for employees’ safety or knowingly allows conditions to persist that are likely to result in serious illness or death.23 In the context of the COVID-19 epidemic, an employer might be liable in a tort suit if, for example, a meatpacking plant or warehouse with a record of positive tests is reopened prematurely, resulting in further outbreaks or a worker’s death.

Longer-term, as states, employers, and workers continue to grapple with the challenges of covering work-related illnesses, including the growing number of “gig economy” workers who are excluded from coverage, they may want to consider these responses and others, both within and outside of workers’ compensation.

References

Abrams, H. (2001). A Short History of Occupational Health. Journal of Public Health Policy, 22(1), 34-80.

Barth, P. & Hunt, H. (1980). Workers’ Compensation and Work-Related Illnesses. Boston, US: MIT Press.

Brandt-Rauf, P. & Brandt-Rauf, S. (1988). Compensation for Occupational Disease: Hidden Agendas.

Health Affairs, 7(4), 73-82.

Boden, L., Murphy, G., & Weiss, E. (2019). Workers’ Compensation Benefits, Costs, and Coverage – 2017 Data. National Academy of Social Insurance.

Burton, J. & Spieler, E. (2012). The Lack of Correspondence Between Work-Related Disability and Receipt of Workers’ Compensation Benefits. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 55, 487-505.

Larson, LK. (2019). Larson’s Workers’ Compensation. New Providence, NJ: Matthew Bender.

Leigh, J. & Robbins, J. (2004). Occupational Disease and Workers’ Compensations: Coverage, Costs, and Consequences. The Millbank Quarterly, 82(4), 689-721.

Schumaker, E. (2020). Timeline: How coronavirus got started. Accessed 4 May 2020, from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/timeline-coronavirus-started/story?id=69435165

Spieler, E. (2017). Reassessing the Grand Bargain: Compensation for Work Injuries in the United States, 1900-2017. Rutgers University Law Review, 69(3), 891-1014.

Appendix: State Workers’ Compensation Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic (as of May 18, 2020)

| State | Law Changed / Pending / No* |

Legislative vs. Executive |

Notes/Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | No | N/A | N/A |

| Alaska | Yes | Legislative | Presumption for first responders and health care employees (full text). |

| Arizona | No | N/A | N/A |

| Arkansas | Yes | Executive | Suspends certain provisions of Arkansas Code to allow healthcare workers, first responders, and AR National Guard to seek worker’s compensation for contraction of or exposure to COVID-19 (EO 20-19; EO 20-22). |

| California | Yes, further action pending | Executive | Rebuttal presumption for all workers that (1) test positive for COVID-19 within 14 days after performing work or (2) are diagnosed (within 14 days of performing work) by a physician and have that diagnosis confirmed within 30 days of the original diagnosis date via a laboratory test (EO N-62-20). |

| Colorado | No | N/A | N/A |

| Connecticut | No | N/A | N/A |

| Delaware | No | N/A | N/A |

| District of Columbia | No | N/A | N/A |

| Florida | Yes | Executive | Presumption for “frontline” state employees only.24 Head of any executive or cabinet agency may opt out of these provisions via written notice to Department of Financial Services (CFO Directive). |

| Georgia | No | N/A | N/A |

| Hawaii | No | N/A | N/A |

| Idaho | No | N/A | N/A |

| Illinois | No | N/A | Workers’ compensation amendment withdrawn after court struck down |

| Indiana | No | N/A | N/A |

| Iowa | No | N/A | N/A |

| Kansas | No | N/A | N/A |

| Kentucky | Yes | Executive | Presumption that COVID-19 exposure was work-related for first responders, health care workers, grocery workers, and others as defined in EO 2020-277. Entitles these workers to TTD payments during period of self-quarantine (EO 2020-277). |

| Louisiana | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| Maine | No | N/A | N/A |

| Maryland | No | N/A | N/A |

| Massachusetts | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| Michigan | Yes, further action pending | Executive | Rebuttal presumption for first responders and health care employees, remains in effect until 9/30/20 (emergency rules). |

| Minnesota | Yes | Legislative | Presumption for first responders, home care workers, corrections officers, and others (full text). |

| Mississippi | No | N/A | N/A |

| Missouri | Yes | Executive | Rebuttal presumption for first responders (defined in Section 287.243; emergency rules). |

| Montana | No | N/A | N/A |

| Nebraska | No | N/A | N/A |

| Nevada | No | N/A | N/A |

| New Hampshire | Yesᶧ | Executive | Presumption for first responders (e.g., emergency medical personnel) as defined in RSA 281-A:2 V-c (emergency orders). |

| New Jersey | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| New Mexico | Yesᶧ | Executive | Presumption for all state employees, certain medical professionals, and eligible volunteers (EO 2020-025). |

| New York | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| North Carolina | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| North Dakota | Yes | Executive | Extends coverage for first responders, front-line health care workers, and funeral home personnel who contract COVID-19, who must show that it was a work-related exposure. Eligible for 14 days of wage replacement (if not covered by any other insurance policy) if these workers are subject to quarantine (EO 2020-12; EO |

| Ohio | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| Oklahoma | No | N/A | N/A |

| Oregon | No | N/A | N/A |

| Pennsylvania | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| Rhode Island | No | N/A | N/A |

| South Carolina | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| South Dakota | No | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee | No | N/A | N/A |

| Texas | No | N/A | N/A |

| Utah | Yes | Legislative | Rebuttal presumption for first responders (including volunteers) and health care workers for claims between 3/21 and 6/1 (full text). |

| Vermont | Pending | N/A | N/A |

| Virginia | No | N/A | N/A |

| Washington | Yes | Executive | First state to issue COVID-related change. Presumption for first responders, health care workers (press release). |

| West Virginia | No | N/A | N/A |

| Wisconsin | Yes | Legislative | Rebuttal presumption for first responders [includes volunteers and employees who administer medical treatment] (full text). |

| Wyoming | No | N/A | N/A |

*National Review article list, plus link to comprehensive list of all states’ actions: https://ogletree.com/app/uploads/covid-19/COVID-19-Workers-Compensation-Coverage.pdf?Version=1 (Accessed May 10, 2020)

National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI) State Activity Tracker: https://www.ncci.com/Articles/Documents/II_Covid-19-Presumptions.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2020)

dddddddddddddddddd