Elaine Weiss, Lead Policy Analyst for Income Security; Jay Patel, Research Assistant

Workers’ compensation experts have expressed concern in recent years about the impact of decades of state cost-cutting measures and resulting uneven and increasingly inadequate benefits for injured workers.[1] Indeed, a ProPublica investigation reveals the steep decline in compensation for disabling injuries, including cutting off benefits long before many workers have recovered and refusing coverage for necessary aspects of care: “Over the past decade, state after state has been dismantling America’s workers’ comp system with disastrous consequences for many of the hundreds of thousands of people who suffer serious injuries at work each year.”[2]

It can be difficult to assess the disparities across states, however, and comparisons often produce invalid conclusions.

Most historical accounts of the U.S. Workers’ Compensation system – including those of the Academy – begin around the turn of the 20th century. That was when advocates like Crystal Eastman and Jane Addams, with help from President Roosevelt, helped call attention to the catastrophic numbers of serious injuries suffered, mostly uncompensated, by American laborers. Nods are paid, too, in these accounts, to the German system that helped inspire U.S. state-level workers’ compensation programs.

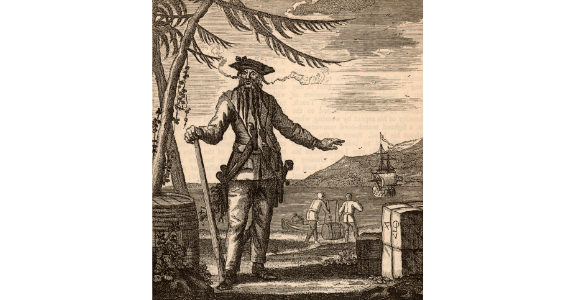

But those accounts leave out a much earlier piece of history: a form of worker’s compensation dating back to the 1650s onboard pirate ships. In his memoirs, Alexandre Exquemelin, a crew member of Captain Henry Morgan’s ship, describes the ‘laws’ that all of the Captain’s pirates followed. These include a detailed loss-of-limb schedule[3] – remarkably similar to those used in most states today, which offers a unique opportunity to make interesting historical comparisons. Here, we use ‘weeks of pay’ to assess how states stack up against one another in one aspect of compensation for two specific types of serious work-related injuries, as well as how they compare to seventeenth-century pirates.

Check out the tables below to see how your state’s benefits compare to pirate policy.

Finally, accounts of pirate-era laws raise another interesting question and potential point of comparison. Injured pirates also had an extra layer of insurance; those who could no longer perform tasks like capturing enemies or wielding daggers were guaranteed work as cooks or deck-hands. So perhaps another comparison worth exploring is the degree to which modern-day U.S. states provide any comparable post-injury employment guarantees or opportunities.

[1] See, e.g., Boden, Reville, and Biddle, 2005, and Spieler, 2017.

<[2] Grabell and Berkes, 2015.

[3] The History of Buccaneers of America (1699), p. 40.

With the exception of Massachusetts, U.S. states have done well on compensating for the loss of eyes

|

Less than Pirates |

Equivalent |

More Generous than Pirates |

Data Not Available/ Unclear |

|

Massachusetts |

|

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming (federal employees) |

Alaska, California, Florida, Indiana, Minnesota, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Texas, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia |

Not nearly as well on loss of arms

|

Less than Pirates |

Equivalent |

More Generous than Pirates |

Data Not Available/ Unclear |

| Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, Wyoming | Maine, Michigan, Oklahoma, | District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Kentucky, Maryland, Montana, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Wisconsin (federal employees) | Alaska, California, Florida, Indiana, Minnesota, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Texas, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia

|

References

Addams, Jane, Twenty Years at Hull-House, University of Illinois Press.

Basic Legal Citation. (n.d.). Accessed 27 January 2020, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/citation/3-300#3-320_Alabama

Boden, Leslie I., Robert T. Reville, and Jeff Biddle. 2005. “The Adequacy of Workers’ Compensation Cash Benefits.” Workplace Injuries and Diseases: Prevention and Compensation—Essays in Honor of Terry Thomason, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research: 37-68.

Compensation for certain permanent injuries, Del. Code § 19-23-2326.

Compensation For Disability, Ala. Code § 25-5-57.

Compensation for disability – Scheduled permanent injuries, Ark. Code § 11-9-521 (LexisNexis).

Compensation for disability, Fla. Stat. § 440.15.

Compensation for partial disability: computation, A.R.S. § 23-1044.

Compensation for permanent partial disability, O.C.G.A. § 34-9-263.

Compensation schedule, D.C. Code § 1-623.07.

Eastman, Crystal. 1910. Work Accidents and the Law. Russell Sage Foundation.

Exquemelin, A.O. (1699). The history of the bucaniers of America from their first original down to this time, written in several languages, and now collected into one volume… London, UK: Printed for Tho. Newborough, John Nicholson, and Benj. Tooke.

How Much Are Workers’ Compensation Benefits in Indiana? (n.d.) Accessed 20 January 2020, from https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/how-much-are-workers-compensation-benefits-in-indiana.html

Grabell, Michael and Howard Berkes, “The Demolition of Workers’ Comp.” ProPublica. March 4, 2015. https://www.propublica.org/article/the-demolition-of-workers-compensation.

Michigan State University. (2008). PPD Benefits by State. Accessed 20 January 2020, from https://hrlr.msu.edu/hr_executive_education/documents/State20PPD20Laws2008-02.pdf

Partial Disability, H.R.S. § 386-32.

Permanent disabilities, Iowa Code § 85.34

Permanent Partial Disability Benefits For Scheduled Injuries, C.R.S. § 8-42-107(2).

SCHEDULED INCOME BENEFITS FOR LOSS OR LOSSES OF USE OF BODILY MEMBERS, Idaho Code § 72-428.

Skowronski, J. (2018). Hurt on the job? A state-by-state guide to workers’ compensation. Accessed 20 January 2020, from https://www.policygenius.com/blog/state-by-state-guide-to-workers-compensation/

Spieler, Emily A. 2017. “(Re)assessing the Grand Bargain: Compensation for Work Injuries in the United States, 1900-2017.” Rutgers University Law Review 69:891-1014.

State of Connecticut Workers’ Compensation Commission. (n.d.). Information Packet. Accessed 20 January 2020, from https://wcc.state.ct.us/download/acrobat/Info-Packet.pdf

Workers’ Compensation Act, 820 ILCS 305/8.

Basically everything and nothing has changed since I published a book called DEATH ON THE JOB: occupational health and

safety struggles in the United States (1978). Workers’ comp screwinjured s workers more than in the mid-1970s when I was collecting

and publishing the existing data, esp. the permanently disabled. John Burton, who ably ably headed up the Nixon Commission created by the 1970 OSHA Law by who told me that back in about 1972 in Chicago when we chatted, that was the only one of two Republican in academic who knew anything about workers’ comp so Nixon chose him to run the Nixon Comission. Check out in my DEATH ON THE JOB ch. 1: “History), ch. 3: “How Cheap Is a Life? and the Tables at the end of the book. Grabell & Berkes’ in Demolition of Workers’ Compensation, and anything Les Boden writes ably explain how bad it got from 2003-2013/’14, but of of course it’s worse for injured workers,esp the permanently disabled who are the most costly and need it the most. WC is an insiders’ game, with ONLY employers and insurance cos. on the inside!!! Dan Berman danmberman@gmail.com Nov. 15, 2021