William Spriggs, Chief Economist, AFL-CIO

William Arnone, Chief Executive Officer

Is there a social insurance response to the many economic, health, and other risks that climate change is generating?

The myriad risks posed by climate change were not envisioned during the Great Depression, out of which much of our nation’s social insurance infrastructure emerged. The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 did not affect the heart of American economic activity, and was treated as an outlier, “a once in a life-time” event too unlikely to re-occur to get incorporated in actual long-term policy planning.

Today, however, “climate change makes extreme flooding more likely. Hotter air and ocean temperatures fuel larger storms and intensify precipitation, as the 2014 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report confirms. And sea level rise almost by definition increases flood risk, due to more water volume and higher inland storm surges. Combine that with the fact that nearly 40 percent of Americans live near the coast, and Houston, we have a problem” (David Dayen, “This Is What Flood Denialism Looks Like,” The New Republic).

“(C)hanging climate is the driving force behind human history.” – Nels Winkless III and Iben Browning, Climate and the Affairs of Men, Fraser Publishing, Burlington, VT, 1975

Existing Protections against Regular Occurrences of Extreme Weather

For example: Flood Insurance

The National Flood Insurance Program, which was created in 1968 after most private insurers stopped selling flood policies or charged very high premiums, provides mandatory insurance in areas labeled a flood risk, with claims funded through mandatory premiums paid by homeowners. David Dayen writes, however, that the program is “a massive, wasteful, and unnecessary giveaway.” Dayen further points out how severe weather events have overwhelmed the program. Hurricane Katrina (and two others in 2005) triggered $19 billion in borrowing from the Treasury, after which Superstorm Sandy added another $10 billion in claims. Congress has enacted many short-term reauthorizations to address the program’s funding shortfalls.

Federal law requires homeowners to have insurance, if they have a federally-backed mortgage and live in a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) designated area in which there is at least a one-percent annual probability of flooding. (Basic home insurance policies, which are also required for most mortgages, cover the contents of home, but not damage caused by floods.)

Over 40 million Americans live in such areas, but fewer than one-third have purchased such insurance. Many homes in some low-income neighborhoods are owned by absentee landlords who do not have mortgages, and so are subject to no requirement to carry flood insurance (“Few Bother to Buy It, But Many Will Still Need it,” New York Times, September 20, 2018). In short, as a New York Times editorial noted, the program “fails to account for the full extent of flood risk, encourages development in areas known to be flood prone and is not realistically funded” (“The Holes in Flood Insurance,” September 1, 2017).

Furthermore, Squared Away’s Kim Blanton notes that the “potential financial risks from flooding are steepest for lower-income homeowners…(who) may lack the resources to pay the deductibles on their flood insurance or…to pay for repairs that exceed the coverage limits set by the policy.”

Economic Security Implications

Extreme weather as a result of climate change poses major threats and ever greater risks to incomes, assets, and even lives. Flooding and fire-ravaged California are just the latest in a long string of dire examples. Floods, hurricanes, and fires threaten the values of one of the most important household (and retirement) assets of many Americans – their homes. However, home loss is only one element. Major flooding across the nation also has the potential to disrupt important economic activities. Small businesses may find it hard to retain their employees if a catastrophe occurs. They often lack the funds to keep employees on the payroll, if a flood or fire causes them to shut down for a week. While the Department of Labor does have an Unemployment Insurance scheme to cover workers hurt by disasters, it might be too cumbersome to put in place for shorter disasters, although for many workers that may mean the loss of a week’s pay. For low-wage workers, losing one-fourth of their monthly income may spell disaster.

As a result of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire disaster, in which 146 workers died, more states began adopting protections for workers, including Workers’ Compensation laws, which constitute the oldest form of social insurance in the U.S. (Image first published on the front page of The New York World 1911-01-26)

When storms or fires disrupt economic activity in major economic centers, local tax revenues might collapse. Payroll taxes that cover a state’s Unemployment Insurance system, and lodging taxes that cities may use for schools or special projects, dry up. When the economy of New Orleans was disrupted, it stopped cash flow from the majority of tax sources for the state of Louisiana. State governments are ill-prepared to run sizeable unexpected deficits. Because state and local governments must balance their budgets, big cash shortfalls invariably force cuts to education, infrastructure, and health programs. We are seeing how difficult the problems caused by Hurricane Maria have been for Puerto Rico to overcome. Its economy was already weakened from the Great Recession, but the storm disrupted revenue and damaged infrastructure that created a public finance crisis exacerbated by accelerating the loss of population. This has made it more economically fragile to other crisis not related to climate, like its current earthquakes.

Recent studies issued by the Federal Reserve raise the specter of the implications of climate change for home values, flood-prone communities, bank lending practices, and other aspects of our economy. Focused on “preparing vulnerable regions most at risk for a ‘new abnormal,’” the San Francisco Fed just published (in October 2019) a series of papers that examine the various financial risks of climate change and associated severe weather events across the country.

In response to the practice of “blue-lining,” in which banks avoid lending to flood-prone areas, is it not time to consider a social insurance approach to flooding and other environmental risks, as an alternative to relying on often over-stretched real estate tax bases in such areas? And is it just a matter of time before even affluent cities face the same threats to their safety and security? The private insurance industry, even with an efficient re-insurance market, may push costs higher for everyone, as it struggles to keep pace with rising claims. Might a social insurance approach provide more effective coverage to those most at risk?

Social insurance is a time-honored and cost-effective response to widespread risks that are often underestimated or ignored by the private sector, or do not offer a market for profits. Risks associated with climate change are also often overwhelming for individuals and communities to insure against on their own, especially when they have no experience dealing with hazards of such magnitude. A collective response may therefore be necessary to provide adequate protection for all, especially the most vulnerable. Might we develop and implement a social insurance approach that is able to deliver financial relief quickly and efficiently to maintain economic activity and cushion displacement?

A Major Challenge Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

For example: Flint’s Water Crisis

In 2014, officials from Flint, Michigan switched the city’s water supply from Detroit’s system to the heavily polluted Flint River as a cost-cutting measure. In doing so, they failed to correct their additives and the water leaked lead from the older pipes in homes introducing lead-poisoned water into them, setting in motion a massive public-health crisis.

One of the ensuing risks that residents of Flint have faced is foreclosure on their water bills. This is not, however, a factor of running water being expensive. Rather, as the city’s population has shrunk in recent years, the need to maintain and update old sewage systems, which represent the bulk of water bills, stayed the same or increased. Residents have been informed that they must go without clean running water. That crisis has revealed similar issues in too many American cities with lead as part of an aged infrastructure.

This reality, which seems unthinkable in the world’s largest and most prosperous economy, reflects the failure of local political economies to provide the necessary infrastructure to deal with environmental change. Isn’t insuring against the loss of water as critical to people’s lives as the traditional social insurance risks of old age, disability, and death? Isn’t providing safe water no less a fundamental obligation of a civilized society? At a time when our nation, and especially its business leaders, express increasing concerns about inequality, who is left trapped in communities like Flint to bear the risk of unsafe water?

Social insurance offers governments an effective mechanism to smooth these types of disruptions and transition to more sustainable policies. In effect, they ensure that neighborhoods affected will continue to exist as livable parts of our societal fabric.

Surveys of Millennials and younger Americans consistently identify climate change as one of their top voting priorities. As the Brookings Institution and the Millennial Action Project noted recently: “More and more Millennials are taking to the streets to demand action on climate change.” Indeed, the global climate strike in September 2019 drew millions of mostly young supporters worldwide. At the other end of the generational spectrum, Stria issued in April a paper titled, “The Impact of Climate Change on an Aging America,” which curated articles that addressed the effects of extreme weather on the most vulnerable seniors from physical and health impacts to financial implications.

Naomi Oreskes of Harvard and Nicholas Stern of the London School of Economics recently wrote in The New York Times (“Climate Change’s Unknown Costs,” October 25, 2019) about problems associated with economists underestimating the costs and risks that climate change poses “to lives and livelihoods.” They highlighted a report issued jointly by the London School, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, and the Earth Institute at Columbia University. That report warned that these so-called “missing risks” might have “drastic and potentially catastrophic impacts on citizens, communities, and companies.” Economists in particular, Oreskes and Stern pointed out, “approach climate damages as minor perturbations around an underlying, consistent path of economic growth and take little account of the fundamental destruction that we might be facing because it is so outside humanity’s experience.”

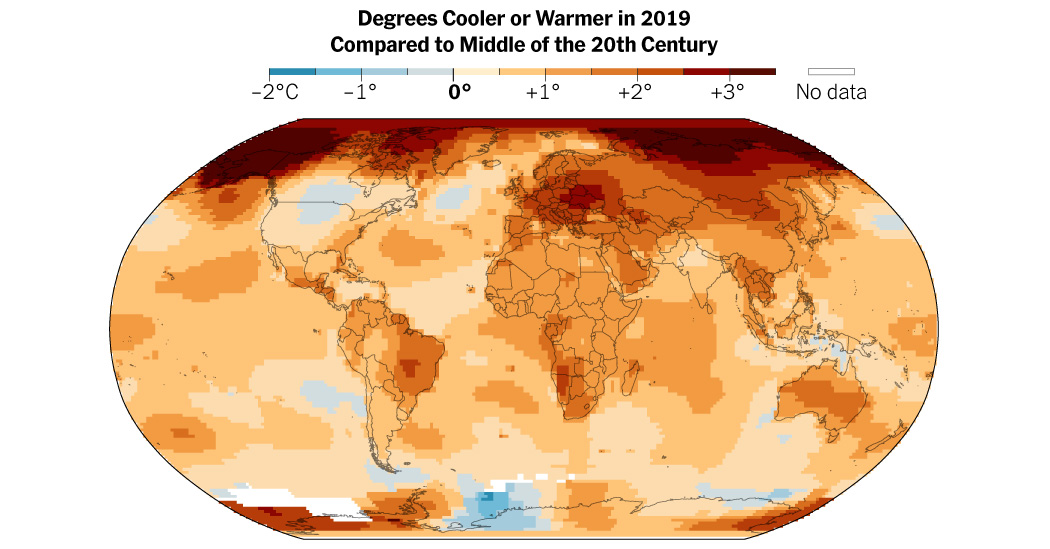

(Image by The New York Times; Source: NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies | Anomalies shown relative to the average temperature at each location between 1951 and 1980.)

What next?

As more voters identify climate change as a key issue, it will continue to garner increasing media attention. Major media outlets are likely to keep the focus on candidates’ proposals to address it, including the “Green New Deal.” The Economist, not necessarily a venue one would expect to dedicate major space to this “non-economic” subject, devoted its entire September 19, 2019 issue to it. More recently, Axios announced that it plans to “take a wholly different approach to election coverage, by focusing on the critical trends that are certain to outlive the moment.” One of their key “topics that matter” is “climate change, and proposed policies to address it, (which) deserve intense scrutiny, free of hyperbole and denial.” This focus should include a discussion of the potential role of social insurance in cushioning the effects of climate change-related displacements.

The winners of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics – Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, joint authors of Good Economics for Hard Times – call for a policy of intelligent interventionism for a society built on compassion and respect. They identify accelerating climate change as one source of global anxiety that might be addressed with appropriate methods and resources. (Source: The November 2019 edition of Commentary, by Academy Member Ken Buffin)

Addressing the challenge of climate change includes a fundamental focus on curbing carbon emissions. As a September 2019 issue of The Economist stated: “To decarbonise an economy is not a simple subtraction; it requires a near complete overhaul.” By looking at how social insurance might address displacement risks generated by a changing climate, we acknowledge the necessity of curbing emissions, while also reducing the economic insecurity that often accompanies major economic transitions.

Climate change-related disruptions were ignored in the aftermath of the Great Recession, when we also largely failed to enact similarly bold and visionary policy responses to what was clearly another major economic earthquake. Our task today is to face this challenge head on, rather than continuing to avoid it. Central to that strategy is regenerating social insurance as a vibrant system that continues to adapt to cover emerging risks.

William Arnone, Chief Executive Officer, National Academy of Social Insurance

William Spriggs, Chief Economist, AFL-CIO

William Spriggs, Chief Economist, AFL-CIO